Which Ethics Review Boards Are Available to Review Women and Child Study in Nepal_

- Research

- Open Admission

- Published:

Causes and age of neonatal death and associations with maternal and newborn care characteristics in Nepal: a verbal autopsy study

Archives of Public Health volume 80, Article number:26 (2022) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

In Nepal, neonatal bloodshed fell substantially between 2000 and 2018, decreasing 50% from 40 to 20 deaths per one,000 live births. Nepal's success has been attributed to a decreasing total fertility rate, improvements in female education, increases in coverage of skilled care at birth, and community-based child survival interventions.

Methods

A verbal dissection written report, led by the Integrated Rural Health Development Preparation Center (IRHDTC), conducted interviews for 338 neonatal deaths beyond six districts in Nepal between April 2012 and April 2013. We conducted a secondary analysis of verbal autopsy data to empathize how cause and historic period of neonatal decease are related to wellness behaviors, care seeking practices, and coverage of essential services in Nepal.

Results

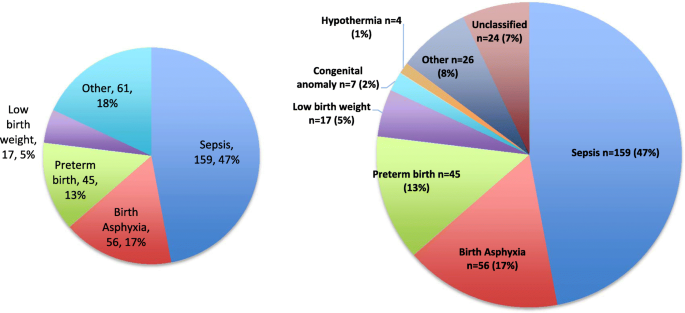

Sepsis was the leading cause of neonatal death (northward=159/338, 47.0%), followed past nascency asphyxia (northward=56/338, 16.6%), preterm nascence (n=45/338, 13.three%), and depression birth weight (n=17/338, 5.0%). Neonatal deaths occurred primarily on the first day of life (27.two%) and betwixt days 1 and 6 (64.viii%) of life. Risk of decease due birth asphyxia relative to sepsis was higher among mothers who were nulligravida, had <4 antenatal care visits, and had a multiple birth; risk of death due to prematurity relative to sepsis was lower for women who made ≥1 delivery preparation and college for women with a multiple birth.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest cause and age of death distributions typically associated with loftier mortality settings. Increased coverage of preventive antenatal intendance interventions and counseling are critically needed. Delays in care seeking for newborn affliction and quality of care around the time of commitment and for sick newborns are of import points of intervention with potential to reduce deaths, particularly for nascence asphyxia and sepsis, which remain mutual in this population.

Groundwork

In Nepal, mortality amid children younger than five years old decreased by 61% from 81 to 32 deaths per 1000 live births between 2000 and 2018 [i]. Amongst newborns, mortality likewise declined, simply at a slower pace, falling 50% from 40 to twenty deaths per 1000 live births [i]. Nepal'due south success has been attributed to a decreasing total fertility rate, improvements in female person education, increases in coverage of skilled care at birth, and customs-based kid survival interventions [2, 3]. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of reducing neonatal mortality to 12 deaths per 1000 alive births by 2030 will require an understanding, across the varied geographical regions in Nepal, of the causes of neonatal death, coverage of critical interventions for newborn survival, newborn care practices, and intendance seeking behaviors during newborn illness [4].

In 2007, Nepal'southward Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP), guided by the National Neonatal Health Strategy 2004, developed the Community-Based Newborn Intendance Package (CB-NCP), a program aimed to evangelize testify-based health interventions targeting leading causes of neonatal bloodshed [5,6,7]. CB-NCP utilized facility-based and community-based health workers, including Female Community Wellness Volunteers (FCHV), who live in the communities where they work, for health promotion activities and commitment of customs-based preventive and therapeutic interventions [five]. The program focused on seven areas: behavior change communication for nascency preparedness and newborn care; promotion of institutional delivery or clean delivery practices in the habitation; recognition and management of nascence asphyxia; postnatal care; care of low birth weight newborns; prevention and management of hypothermia; and direction of newborn infection [5]. Afterwards the plan was piloted in ten districts (2009–2010), it was scaled up across Nepal, and eventually merged with the Customs-Based Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (CB-IMCI) in 2015 to create a unified arroyo (CB-IMNCI) to child survival [eight, ix].

Understanding how neonatal bloodshed and morbidity are related to coverage of wellness interventions promoted by CB-IMNCI, also as care seeking behaviors and management of newborn illness, are critical to improving survival for mothers and their babies [x,xi,12]. Verbal autopsy is a widely-used methodology for determining cause of death in populations without a complete vital registration system [13]. Such surveys include questions about the clinical signs and symptoms, health behaviors and care seeking, and increasingly, social factors that touch on access to intendance and health outcomes [14]. We conducted a secondary data analysis of data collected through a verbal autopsy written report in six districts in Nepal between 2012 and 2013 to improve understand how these factors were related to crusade and age of newborn death.

Methods

Report design

This written report was a descriptive secondary analysis of the associations between two outcomes – causes of death and historic period of death – and participant factors, including maternal characteristics, health care service utilization, and care seeking behaviors for neonatal deaths collected from 6 districts in Nepal between Apr 13, 2012, and April 13, 2013 (Nepali fiscal year 2069/2070). The original study was designed and implemented by a not-profit organization, the Integrated Rural Health Evolution Training Centre (IRHDTC), based in Kathmandu, Nepal, in collaboration with the Kid Health Division, MoHP [15].

Every bit atomic number 82 of the original report, IRHDTC constructed the report sample with the aim of including all neonatal deaths in Dolpa, Jumla, Morang, Chitwan, Palpa, and Salyan districts over the study period. The report also aimed to identify stillbirths; all the same, high data missingness precluded their inclusion in this analysis. Districts were selected to correspond Nepal's three ecological areas: mountain, hill, and Terai (plains), from among those that had implemented the CB-NCP for at to the lowest degree one year. In each district, IRHDTC identified neonatal deaths for inclusion past reviewing multiple data sources, beginning with CB-NCP reports at the District Health Office (DHO) or District Public Wellness Office (DPHO). FCHVs were responsible for completing these reports for deaths that occurred outside of a facility as part of their antenatal and post-partum habitation visits, which ran until the 28th twenty-four hours of life. Information in the CB-NCP database were and then verified at the wellness facility by the IRHDTC team. This primary data collection occurred from September to December 2013.

Verbal autopsy interviews

IRHDTC developed a verbal autopsy questionnaire to define the cause of neonatal death through a two-mean solar day consultative workshop with representatives from MoHP, Family Wellness Partitioning (FHD), Kid Health Division (CHD), and several non-profit organizations. The questionnaire was designed using a standard verbal autopsy methodology described by the World Wellness Organization (WHO) [13]. The questionnaire included an open-concluded narrative and closed-ended questions to collect data on the vital statistics of the deceased newborn, morbidity history of the newborn, maternal demographic characteristics, pregnancy and commitment history, essential newborn intendance practices, and care seeking behaviors during newborn disease.

Written report interviewers, who administered the exact autopsy questionnaire, were non-clinical public health professionals with a minimum of a bachelor level degree in a health field. Preference was given to interviewers with prior training or feel working with the CB-NCP. Interviewers participated in a iv-twenty-four hours training on the verbal autopsy questionnaire, including a field trip to Kavre to pre-test the report tools. Study pediatricians conducted the training, covering the aim and objectives of the study, methodology, data collection procedures and tools, components of the CB-NCP, and research ideals.

After identification of neonatal deaths, interviewers visited households of the deceased newborn to interview the female parent or the adjacent of kin available who had spent the longest corporeality of time with the baby during disease and prior to death (Additional file 1). Local community wellness workers joined interviewers to facilitate the interview and serve as translators. Field coordinators reviewed data for ten% of the neonatal deaths to bank check for accurateness, completeness, and consistency. Interviews were conducted under the direction of the principal investigator of the original study, a pediatrician from IRHDTC (JRD).

Cause of death assignment

IRHDTC conducted the crusade of expiry assignment during the original study, after completion of master data collection and prior to the start of this secondary analysis. A single cause of death was independently assigned for each case past ii pediatricians in the IRHDTC research team using a modified version of the Neonatal and Intrauterine Expiry Classification according to Etiology (NICE) methodology [sixteen]. In the result of conflict in the conclusion of classification of a death, the two pediatricians attempted to resolve the issue through discussion. If no consensus could exist reached, a concluding determination of classification was made by a 3rd physician, the principal investigator (JRD).

Statistical analysis

In this secondary analysis, we explored relationships between crusade of neonatal death and age of death and risk factors among a sample of live born newborns who died within 28 days of life. Determinants were categorized as: maternal demographic characteristics, antenatal health care utilization, pregnancy and delivery characteristics, and newborn care practices and care seeking practices during newborn illness. We conducted bivariate analyses, reporting numbers and percentages, and assessed differences betwixt crusade and historic period of decease groups and participant characteristics using chi-squared tests. Associations between age of newborn death and risk factors were displayed in Kaplan-Meier graphs and evaluated using log-rank tests. Factors associated with cause of death and age of expiry in bivariate analyses (p < 0.05) with < 15% missing information, too every bit other factors known from the literature to be risk factors for these outcomes, were included in multivariable regression modeling. In cases where two like factors met these criteria (e.g., ANC visit attendance and tetanus immunization), one was selected for inclusion in the regression modeling. Separate multinomial logistic regression models were used to estimate relative run a risk ratios and 95% conviction intervals (CIs) between these factors and the ii outcomes of involvement: crusade and age of death. As a non-expiry reference group was non available in these data, the sepsis cause of death was selected to serve equally the reference category for these analyses because it had the largest number of cases. For the purpose of making general comparisons, we included data from Nepal 2016 Demographic and Wellness Surveys (DHS) where available [17]. Analyses were conducted in Stata version fourteen.2.

Results

Causes of expiry for 338 newborns, as assigned by the original verbal dissection study team, are presented in Fig. 1. A quarter (due north = 89, 26.3%) of neonatal deaths occurred among babies built-in preterm (< 37 weeks) (term: northward = 206, 61.0%; mail service-term: n = 43, 12.7%). Of the deaths with a known nativity weight, 39.iii% (northward = 81/206) were depression birth weight (< 2500 g). Of the infants that were preterm, 48.3% (n = 43) were assigned a crusade of death of "prematurity-related," and of those that were low birth weight, 18.five% (n = fifteen) were assigned a cause of death of "LBW-related." Approximately a quarter (n = 92, 27.2%) of deaths occurred on the day of birth (day 0), and nearly two-thirds (n = 219, 64.8%) occurred in the starting time week (0 to 6 days). Age of expiry (overall mean of 6.ii days (interquartile range: 0 to 10 days)) differed statistically significantly (p < 0.001) by crusade of death, with deaths from birth asphyxia, low birth weight, and preterm birth, occurring earlier than those from sepsis.

Cause of death distribution for newborns (due north = 338) in half dozen districts of Nepal from Apr 2012 to Apr 2013. Number and percent of deaths by crusade for newborns (due north = 338) in six districts of Nepal from April 2012 to Apr 2013. The other category included respiratory distress syndrome (due north = half-dozen, 1.8%), meconium aspiration syndrome (due north = 5, 1.5%), birth injury (n = two, 0.vi%), severe jaundice (n = i, 0.3%), and others (northward = 12, 3.6%)

Demographic characteristics

Cause of neonatal death was not significantly unlike across the half dozen written report districts (p = 0.321). Infant sexual activity (n = 191, 56.5% male) varied by district (p = 0.015) (percent male person: Dolpa (75.0%), Salyan (73.ii%), Morang (59.3%), Jumla (56.8%), Palpa (47.7%), and Chitwan (45.9%)). Baby sex, maternal age, religion, caste, smoking, alcohol employ, education, and literacy were not associated with cause of decease (Tabular array one). Crusade of death varied significantly past maternal gravidity, with a higher proportion of women never previously pregnant occurring among deaths due to birth asphyxia and a lower proportion among sepsis and prematurity (p = 0.032). Of the demographic characteristics, only maternal age was related to age of neonatal death. Younger and older women were observed in higher proportions among deaths that occurred on the twenty-four hours of birth (p = 0.011) (Supplement Fig. one).

Antenatal care utilization

Higher proportions of women with fewer ANC visits occurred among deaths due to neonatal sepsis and prematurity, relative to birth asphyxia (p = 0.037) (Tabular array two). A similar pattern was observed for mothers who received < 2 doses of tetanus toxoid amid deaths due to sepsis and depression nativity weight (p = 0.006). A higher proportion of women who did not make delivery preparations was seen among deaths due to prematurity or other causes, relative to sepsis (p = 0.012). Merely preparations for delivery was associated with age of death, with deaths on the mean solar day of birth having a higher proportion of mothers who made no delivery preparations (Day 0: n = 37/92, 40.two%, Days 1–27: n = 70/246, 28.five%) (p = 0.039).

Pregnancy and labor and delivery characteristics

Multiple birth was significantly related to cause and historic period of neonatal expiry, with a higher proportion occurring among deaths due birth asphyxia and prematurity and lower amongst sepsis and other causes (p = 0.007). Deaths for multiple births (Twenty-four hour period 0: n = 10/92, 10.9%, Days 1–vi: n = 7/127, 5.5%, Days 7–27: northward = 3/119, 2.5%) (p = 0.038) and mothers attended during delivery by an SBA or other health worker (Twenty-four hour period 0: 16/34, 47.1%, Days 1–6: northward = half dozen/41, xiv.half-dozen%, Days 7–27: fourteen/41, 34.2%) (p = 0.009) were observed in higher proportions on the solar day of birth. Maternal complications during pregnancy and labor and delivery are reported in Supplement Table 1.

Newborn intendance practices and intendance seeking behaviors

None of the newborn intendance practices assessed were associated with cause of expiry (Supplement Tabular array ii). Amongst care seeking behaviors for newborn disease, receiving advice from a health worker to seek care was more mutual among deaths due to sepsis and less amid prematurity and other causes (p = 0.002) (Supplement Table 3). Deaths occurring at a health facility, relative to home or other, were observed in higher proportions among deaths due birth asphyxia, prematurity, or low birth weight, and lower for sepsis (p = 0.032). Mothers having received advice to seek care occurred in college proportions amid afterward deaths (Day 0: due north = 9/37, 24.iii%, Days 1–six: n = 45/83, 54.2%, and Days vii–27: n = 64/96, 66.7%) (p < 0.001).

Multinomial logistic regression models

Relative risk ratios for causes and age of death are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Women with no previous pregnancies (aRR 2.58, 95% CI: 1.15, v.83), ≥4 ANC visits (aRR 2.79, 95% CI: 1.30, 5.99) and multiple births (aRR 5.37, 95% CI: 1.40, twenty.58) were more than probable to have a child who died from nativity asphyxia relative to sepsis. Mothers who made ≥1 delivery preparation (aRR 0.35, 95% CI: 0.16, 0.77) were less probable, and women with a multiple birth (aRR vi.12, 95% CI: 1.68, 22.34) more likely, to have a child who died from prematurity than sepsis. Women who were younger (< 20 vs. ≥twenty- < 30 years) were less likely to accept a death occur between Days 1–6 (aRR 0.35, 95% CI: 0.17, 0.72) or Days seven–28 (aRR 0.34, 95% CI: 0.16, 0.71) relative to Day 0. Women with ≥one delivery preparation (aRR 2.00, 95% CI: i.03 3.91) were more than likely, and those who had a multiple birth (aRR 0.17, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.67) less likely, to have a child who died between Days 7–28 relative to Day 0.

Discussion

We conducted a secondary analysis of data from a verbal autopsy study to understand how crusade and age of death differed past demographic, antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal care factors among neonatal deaths in six districts of Nepal between April 2012 and April 2013. Leading causes of death were sepsis (47.0%), birth asphyxia (16.half-dozen%), and preterm nascency (xiii.3%). A high proportion (26.3%) of neonatal deaths were preterm compared to Nepal's national average in 2012 (14%), indicating, as expected, that the risk of expiry was higher among preterm babies than those born total term [xviii,19,twenty].

Verbal autopsy data from Nepal's 2016 Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) presented a different moving-picture show of neonatal bloodshed; leading causes were: respiratory and cardiovascular disorders of the perinatal menstruum (31%); complications of pregnancy, labor, and commitment (30%); infection (16%); and congenital malformations and deformations (7%) [17]. Definitive conclusions virtually these two distributions cannot be drawn because of differences in the cause of expiry assignment methodology used by the NDHS 2016 (World Health Arrangement International Classification of Disease (ICD) 10) and this verbal dissection study (Squeamish). Notwithstanding, the bloodshed distribution reported in our analysis may indicate that the truthful underlying neonatal bloodshed charge per unit in these half dozen districts is high; in such loftier bloodshed settings, deaths related to infection generally represent a larger proportion of total deaths [21, 22]. Alternatively, this could advise that a large proportion of very early neonatal deaths, which are more than probable to occur amongst preterm and asphyxiated babies, were underreported or misclassified as stillbirths in our report [23].

Age of death among newborns in our assay was loftier, and the distribution of deaths over the neonatal period was less right skewed than expected. Only 27.2% of neonatal deaths occurred on the get-go day of life and 64.8% in the first week. This compares to global averages from 2012 of 36 and 73%, respectively, and 57 and 80% from the NDHS 2016 [17, 24]. Similar to the cause of death results, this suggests either a truthful high neonatal mortality rate or that the exact autopsy survey missed, or misclassified as stillbirths, many deaths occurring effectually the time of birth and early days of life. Age of expiry differed past cause of death, driven primarily by deaths from sepsis, which tended to occur later. Every bit expected, preterm babies tended to dice earlier than full term or postal service-term babies. A trend is visible in the graph of age of neonatal death by maternal age, with younger and older mothers tending to accept newborns who die earlier. Higher risk in the youngest historic period group raises concern given the big proportion of immature mothers in Nepal.

Demographic characteristics, including maternal education, literacy, and commune, were unassociated with cause and age of neonatal death. Even so, the baby sex ratio varied widely past commune, and was highest in Dolpa (3-quarters male). Globally, studies take reported a biological survival reward for girls in the early neonatal period; although in South asia, evidence has indicated a higher risk of mortality among girls, especially in the late neonatal period, an observation attributed to differences in intendance seeking and gender preference [25,26,27]. In this context, variation in the infant sex ratio suggests that female person deaths may have been underreported. Maternal gravidity varied by cause of decease, with women having never been previously pregnant at higher take chances of having a neonatal death due to birth asphyxia, an expected result given immature maternal age and nulligravida/nulliparity are risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes [28]. This suggests a need to ensure immature women and first-time mothers are reached with counselling messages and preventive interventions, specially related to nativity preparation and institutional delivery.

Coverage of antenatal intendance and labor and delivery interventions were depression among mothers, especially receiving all four ANC visits, institutional delivery, and skilled attendance at nativity. Beyond Nepal, coverage of these life-saving interventions, although higher than seen in our report population, remain beneath recommended levels, with only 69% of mothers receiving four or more ANC visits and 58% delivered by a skilled provider in 2016 [17]. Several factors relating to contact with the health system during pregnancy, including ANC visits, were associated with a greater proportion of deaths from nativity asphyxia relative to other causes. A likely explanation is reporting bias resultant from an increased likelihood of identifying neonatal deaths due to birth asphyxia and other early on causes of death amidst women who utilized ANC and delivery related services. Alternatively, health workers may have been less likely to refer seemingly healthier pregnant women for ANC. Yet, increased coverage of health services alone may not improve survival if care is non of sufficient quality; a study from the Terai region of Nepal suggested that despite the recent rapid increase in institutional deliveries, homo resources allocations, health worker knowledge, and stocking of equipment and supplies may non be keeping step [29].

Of the pregnancy and labor characteristics, only multiple birth was related to cause of death, with multiple births having a college proportion of deaths attributed to preterm nascency and nascence asphyxia, an expected issue, as the status is a known risk gene for these outcomes [xxx, 31]. No pregnant relationships were identified for newborn care practices and crusade of death. Still, within intendance seeking practices, existence advised past a health worker to seek care was associated with higher risk of death from sepsis in a bivariate analysis. This could exist a result of referral bias, that is, children with severe illness are more probable to be referred, just may not attain care in time to foreclose death. A tendency towards a greater proportion of sepsis deaths occurring at dwelling or on the way to the wellness facility, equally compared to at a health facility, was observed in bivariate analyses but not the last regression model. This could suggest either that sepsis is more difficult for mothers and caregivers to recognize relative to other illnesses or individuals with sepsis who reach a health facility are less likely to dice from the condition. Other studies have highlighted the importance of delays in intendance seeking for newborn illness in Nepal, specially inability of caretakers to recognize danger signs, delays in the decision to seek care, delays related to first use of home remedies or drugs from a chemist's, and overreliance on informal providers [32,33,34].

The study had limitations. The number of neonatal deaths was likely underestimated, due to underreporting and difficulties with identifying and recording cases in rural communities and sparsely populated areas, potentially biasing the cause of and age of death estimates. Stillbirths, which have mutual take a chance factors and causes and are frequently misclassified with neonatal deaths, could not exist included in this analysis due to data missingness. Furnishings of referral and reporting biases are a common weakness for the verbal autopsy written report approach, specially in areas without advanced reporting systems for neonatal deaths. Call up bias, associated with a long fourth dimension period between neonatal death and the interview date, may accept contributed to data missingness and quality. The lack of controls or "non-deaths" prevented any private level comparisons making it difficult to draw strong conclusions nigh how these factors are related to crusade and age of death.

Conclusion

We investigated how antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal hazard factors differed by cause and age of neonatal death in six districts of Nepal. Increased coverage of preventive antenatal intendance interventions and counseling are critically needed, peculiarly for young women. Delays in care seeking for newborn disease and quality of care around the time of delivery and for sick newborns are of import points of intervention with potential to reduce deaths, particularly for birth asphyxia and sepsis, which remain common in this population.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- CHD:

-

Child Wellness Sectionalization

- CB-IMCI:

-

Community-Based Integrated Management of Childhood Illness

- CB-NCP:

-

Community-Based Newborn Intendance Package

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DHO:

-

District Health Function

- DPHO:

-

District Public Health Office

- FHD:

-

Family Health Division

- FCHV:

-

Female Customs Health Volunteers

- ICD:

-

International Nomenclature of Affliction

- IRHDTC:

-

Integrated Rural Wellness Development Training Heart

- MoHP:

-

Ministry building of Health and Population

- NDHS:

-

Nepal Demographic and Health Survey

- Nice:

-

Neonatal and Intrauterine Expiry Classification according to Etiology

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

-

Unicef. The Country of the World'due south Children 2019. Children, Food and Diet: Growing well in a changing earth. New York; 2019.

-

Pradhan YV, Upreti SR, Pratap KCN, et al. Newborn survival in Nepal: a decade of modify and future implications. Wellness Policy Plan. 2012;27(Suppl 3):iii57–71.

-

World Health Arrangement. Integrated Management of Babyhood Affliction global survey report. Geneva; 2017.

-

National Planning Commission. Sustainable Evolution Goals. National (preliminary). Report. 2016-2030;2015.

-

Pradhan YV, Upreti SR, Kc NP, Thapa 1000, Shrestha PR, Shedain PR, et al. Fitting community based newborn care bundle into the health systems of Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2011;9(2):119–28.

-

Ministry of Health and Population. National Neonatal Health Strategy. 2004.

-

Ministry building of Health and Population. Nepal'southward Every Newborn Action Plan. 2016.

-

Paudel D, Shrestha IB, Siebeck M, Rehfuess E. Bear on of the community-based newborn care package in Nepal: a quasi-experimental evaluation. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e015285. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015285.

-

Department of Health Services MoHP, Government of Nepal. Annu Rep 2015/2016. 2017.

-

Thaddeus S, Maine D. As well far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(8):1091–110.

-

Mosley HW, LC C. An analytical framework for the study of child survival in developing countries. Popul Dev Rev. 1984;x:25–45. https://doi.org/10.2307/2807954.

-

Claeson Yard, Waldman RJ. The evolution of child health programmes in developing countries: from targeting diseases to targeting people. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(10):1234–45.

-

Anker 1000, Black RE, Coldham C, et al. A standard verbal autopsy method for investigating causes of death in infants and children.; 1999.

-

Kalter HD, Salgado R, Babille 1000, Koffi AK, Black RE. Social autopsy for maternal and child deaths: a comprehensive literature review to examine the concept and the evolution of the method. Popul Health Metr. 2011;9(1):45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7954-9-45.

-

Integrated Rural Health Evolution Grooming Center. A study on verbal autopsy to ascertain causes of neonatal deaths in Nepal 2014. 2014.

-

Winbo IG, Serenius FH, Dahlquist GG, Källén BA. NICE, a new crusade of death classification for stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Neonatal and intrauterine expiry nomenclature according to etiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27(3):499–504. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/27.iii.499.

-

Ministry of Wellness and Population Nepal NE, and Macro International Inc.,. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2016. , Kathmandu: Ministry of Health and Population; 2017.

-

Blencowe H, Cousens South, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, Moller AB, Narwal R, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with fourth dimension trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet. 2012;379(9832):2162–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-four.

-

Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, et al. Built-in also soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reproductive health. 2013;10(Suppl i):S2.

-

Katz J, Lee ACC, Kozuki Due north, Backyard JE, Cousens Southward, Blencowe H, et al. Mortality risk in preterm and small-for-gestational-age infants in depression-income and middle-income countries: a pooled state assay. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):417–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60993-9.

-

Liu L, Oza Southward, Hogan D, Chu Y, Perin J, Zhu J, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000-15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the sustainable development goals. Lancet. 2017;388(10063):3027–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31593-8.

-

Lawn JE, Kinney MV, Blackness RE, et al. Newborn survival: a multi-country analysis of a decade of change. Health Policy Program. 2012;27(Suppl 3):iii6–28.

-

Liu L, Kalter HD, Chu Y, Kazmi N, Koffi AK, Amouzou A, et al. Understanding misclassification between neonatal deaths and stillbirths: empirical prove from Malawi. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0168743. https://doi.org/10.1371/periodical.pone.0168743.

-

Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Oza S, You D, Lee Air-conditioning, Waiswa P, et al. Every newborn: progress, priorities, and potential across survival. Lancet. 2014;384(9938):189–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60496-seven.

-

Drevenstedt GL, Crimmins EM, Vasunilashorn S, Finch CE. The rise and fall of excess male infant mortality. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(xiii):5016–21. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0800221105.

-

Katz J, West KP Jr, Khatry SK, et al. Risk factors for early babe mortality in Sarlahi district. Nepal Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(10):717–25.

-

Rosenstock S, Katz J, Mullany LC, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, Darmstadt GL, et al. Sex activity differences in neonatal mortality in Sarlahi, Nepal: the part of biology and environment. J Epidemiol Customs Health. 2013;67(12):986–91. https://doi.org/ten.1136/jech-2013-202646.

-

Lee ACC, Mullany LC, Tielsch JM, Katz J, Khatry SK, LeClerq South, et al. Take a chance factors for neonatal mortality due to nascence asphyxia in southern Nepal: a prospective. Customs-based Cohort Study Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1381–90. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-1966.

-

Lama TP, Munos MK, Katz J, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, Mullany LC. Cess of facility and health worker readiness to provide quality antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum care in rural southern Nepal. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;twenty(1):xvi. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4871-x.

-

Kozuki N, Katz J, Khatry SK, et al. Take a chance and burden of agin intrapartum-related outcomes associated with not-cephalic and multiple birth in rural Nepal: a prospective accomplice study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4):e013099.

-

Lee ACC, Mullany LC, Tielsch JM, Katz J, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, et al. Incidence of and take a chance factors for neonatal respiratory depression and encephalopathy in rural Sarlahi. Nepal Pediatrics. 2011;128(iv):e915–24. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3590.

-

Lama TP, Khatry SK, Katz J, LeClerq SC, Mullany LC. Illness recognition, decision-making, and care-seeking for maternal and newborn complications: a qualitative study in Sarlahi District. Nepal J Health Popul Nutr. 2017;36(Suppl 1):45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-017-0123-z.

-

Mesko N, Osrin D, Tamang Due south, Shrestha BP, Manandhar DS, Manandhar M, et al. Intendance for perinatal illness in rural Nepal: a descriptive written report with cross-exclusive and qualitative components. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2003;three(1):three. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-3-three.

-

Herbert HK, Lee AC, Chandran A, et al. Intendance seeking for neonatal affliction in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2012;9(three):e1001183. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001183.

Acknowledgements

Give thanks you to Dr. Binod Man Shrestha and Dr. Bal Krishna Kalakheti for meticulously reviewing the neonatal verbal autopsy forms. We would also like to acknowledge the support provided by the Child Health Division, Ministry of Health and Population, Nepal; United states of america Bureau for International Development; Salve the Children, Saving Newborn Lives; H4L Nepalgunj; and I Heart Earth in Dolpa.

Funding

This work was supported by the United States Agency for International Evolution (USAID).

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

DJE, JBL, LCM, and JK conceptualized and designed the secondary analysis of the exact autopsy data. DJE conducted the secondary assay and drafted the manuscript. JBL, LCM, and JK contributed to the analysis. NNB, PRS, and JRD conceptualized the original verbal autopsy study. NNB, PRS, and SK developed the information drove tools, and NNB oversaw data collection. All authors contributed to preparation of the manuscript, interpretation of the results, and manuscript revisions. The author(s) read and approved the last manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Nepal Health Enquiry Council (NHRC). Written consent was obtained from participants in this verbal dissection study.

Consent for publication

Non applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Additional data

Publisher's Annotation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Boosted file 1: Supplement Table i.

Maternal complications during pregnancy and labor and delivery. Supplement Table 2. Crusade of death past newborn care practices. Supplement Table iii. Cause of death by care seeking during newborn illness

Additional file 2: Supplement Fig. i.

Age of decease for newborns (north = 338) in six districts of Nepal by various factors. Histogram of historic period of decease for newborns (n = 338) in half dozen districts of Nepal (Panel A) and Kaplan Meier cumulative mortality graphs for age of death by cause of death (Panel B), maternal age (Panel C), and commune (Console D).

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits apply, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, every bit long every bit you give appropriate credit to the original writer(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and point if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Artistic Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the cloth. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is non permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you lot volition need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/null/ane.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Erchick, D.J., Lackner, J.B., Mullany, 50.C. et al. Causes and historic period of neonatal death and associations with maternal and newborn care characteristics in Nepal: a exact autopsy report. Arch Public Health 80, 26 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-021-00771-v

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-021-00771-v

Keywords

- Nepal

- Newborn

- Neonatal

- Verbal dissection

- Bloodshed

Source: https://archpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13690-021-00771-5

0 Response to "Which Ethics Review Boards Are Available to Review Women and Child Study in Nepal_"

Post a Comment